In ancient Israel, there was no need for Hebrew translation. Most religious traditions were carried down from generation to generation through oral traditions. Story-tellers and the priestly classes would listen and study fervently throughout their entire lives in order to memorize the religious “texts”. For longer still, even after the advent of translation and transcription, the lack of language, reading, and writing skills among the commoners prevented the majority of people from gaining direct access to religious scriptures.

In the early days of the original Hebrew scriptures and up until the days of the Diaspora and the Hellenistic period, there was very little need for translation at all. After the Diaspora or the spread of the Israelite people around the world, as new Jewish communities were established, it would become more common to translate the Canonical scriptures into new languages. Before this period, almost all of the “interpretation” of the canonical scriptures was based on oral traditions. After this period, quality translation services would help propel religion to the forefront around the world. The modern Bible or canonical scriptures have today become the world’s most translated book. Learn more about the world’s most translated book.

It was long held that the ancient Hebrew scriptures were only written down for the first time around 6000 BC or BCE (“Before Christ” or “Before the Common Era”) as it was previously held that this is about the time the written variant of the ancient Hebrew originated. A 2010 report from the Live Science website indicates that this may not be the case however. The report discusses a pottery shard dating back to somewhere around the tenth century BCE, and while it does not boast actual scriptures, it was writing relating to religious beliefs and definitely strong proof that the written Hebrew language was much older than previously believed.

A Brief History of Biblical Translations

The original biblical translations did not come about until some time after the diaspora when a Community of Greek-speaking Israelites determined that it may perhaps be beneficial to be able to read the original Hebrew scriptures or canonical texts. Given that they had accepted Greek as their primary language after the scattering of the Jewish people during the time of the Diaspora, they undertook to translate ancient Hebrew into the Greek of the day. This is now referred to as ancient Greek in the present day and age, not to be confused with the current or modern Greek language. These original Hebrew translations into ancient Greek occurred sometime around the third century BC during the beginning of the Hellenistic period.

Throughout the Hellenistic period, as may be implied by the very name itself, Greek and Aramaic were the most popular languages among the Jewish people. Many of the Hellenistic writings, including the books of the Apocrypha, were written during this period, with most works being translated into Hebrew and Greek. Hebrew was the common language among the priest class, while many of the commoners of the day spoke only Greek or Aramaic.

In fact, much of what is now commonly referred to as the Greek scriptures, the Aramaic scriptures or the New Testament was originally written in Aramaic and then translated into Hebrew and ultimately into Latin. However, throughout the first century CE, Christianity spread rapidly through Rome, and Latin would soon be the translation of choice.

These translations would ultimately lead to the creation of the Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations by the church which would ultimately come to be known as the Roman Catholic diocese. From the second century CE through the fourth century CE, many changes would take place, and ultimately, the church would foment the majority of the canonical translations into Latin.

The Greek would remain equally popular among some of the more orthodox religious groups, ultimately forming what would become the Greek Orthodox variant of Christianity. While it is just a note in passing, the “apocryphal” books that were originally included in canonical texts would be removed from the Latin Vulgate in 1546 while they remain common in the Greek Orthodox bibles.

The Biblical Translations of Ulfilas

Anyone would be hard-pressed to find a translation company today that was capable of completing the herculean translation undertaken by Ulfilas. Even though his translations of the Canonical scriptures were never completed, his accomplishments remain more than impressive.

At the time, the language of the Goths was unwritten. There were no comparable letters or vowels and no way to undertake this biblical translation other than converting the Greek alphabet and using the characters to represent the sounds of the Gothic language.

In essence, what Ulfilas did was to create an entire language from scratch, specifically to translate the Canonical scriptures into a language that the Goths would be able to understand, and ideally, which could be used to convert them into a more Christian community.

Biblical Translation Forbidden?

The christian conversion of the emperor Constantine would see a vast political power go to the church. While it was not technically an act of heresy to translate the bible from the Latin into additional languages, the practice was discouraged by the papal authority and the church.

St. Jerome is the one ultimately most credited for the complete translation of the ancient Hebrew scriptures or Old Testament, and the Greek and Aramaic scriptures or New Testament into Latin. This is the official biblical translation that would ultimately come to be known as the Latin Vulgate.

The reason and purpose behind these biblical translations stemmed from the belief of St. Jerome that “Ignorance of the scriptures” was equal to an “ignorance of the Christ”. (“The” Christ as Christ is a derivative of the ancient Greek word “Christos” meaning “Messiah” or “The Messiah”)

While St. Jerome seemed to have been convinced that the average Roman citizen should have complete access to the scriptures, much of the rest of the world did not speak Latin. As Western civilization continued its fall and lapse into the dark ages, most of those who spoke, read or wrote Latin were among the more well-educated, largely relegated to the priest classes and some members of royalty.

The Church of Rome it would seem, had found favorable circumstances in keeping control of the canonical texts and the translations and interpretations of scripture for the common folk.

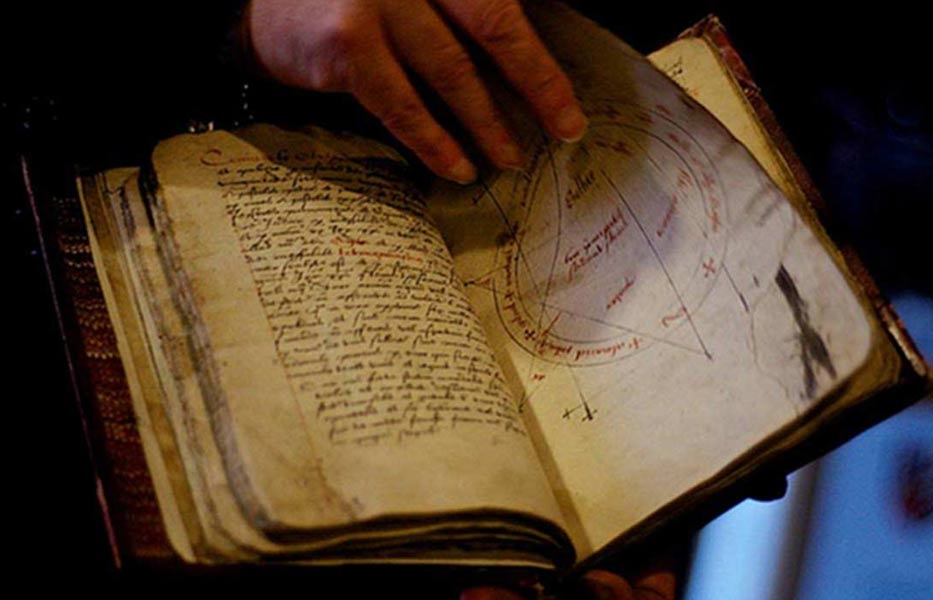

Enter the Scribe and Transcription

Early on in the dark ages, and after the fall of the Roman and ancient Greek empires, schools become more of an anomaly than a common pursuit. Eventually, the Benedictine teachings would be the foundation for what would become educational institutions. Education during the dark ages was a little bit more limited than it is today.

The primary educational centers of the day were Monasteries. It was here also that numerous scribes tediously studied and meticulously transcribed books by hand, largely religious if not canonical in nature. It was not until later in the dark ages that many of the scribes would seek out regular work outside of the monasteries, though even before this, there are some interesting tales, though often difficult to confirm.

The first official version of the first edition of Index Librorum Prohibitorum was not published until 1559 and lasted until 1966. Despite this, there are records indicating that there were unofficial copies dating as far back as the Nicene Creed in 325 CE In 496 CE Pope Gelasius I issued a decree containing lists that included not only books that were recommended but also a clearly defined list of books considered to be heretical and banned for any member of the church.

Among many of the books being banned were those that declared the Roman emperors to be anything other than men, much less godly in stature, bearing or life, save perhaps some history of Constantine. Much of the works of the ancient Greek civilization were also deemed heretical as evidenced by the later battles between the Church of Rome and Galileo, much of whose work was based on that evidence from ancient Greek philosophers and teachers.

While perhaps this little notation should more rightfully be noted as much as conjecture as fact, there remains evidence of ancient texts being translated into Middle English. It would hardly seem possible to believe that the Church of Rome in its battle against heresy and its desire to maintain a monopoly on knowledge would have authorized such translations and transcriptions, especially so early on in the dark ages or middle ages.

Thus it seems logical, that many of these texts must have been commissioned by royalty, at least during the early middle ages. The cost for the level of transcription skills necessary to create a book would remain expensive until the late middle ages and early Renaissance period. Despite this, there are a sufficient number of existing records to indicate that somebody with wealth sought to preserve at least some of the knowledge of the day. Very few people would have had the necessary skills, not only to transcribe but to translate many of these classical works.

It is also interesting to note that before the time of the crusades, there was an ongoing diplomatic relationship with the Muslims until their conquests in Spain. There is a great importance of the middle east common to both Muslims and Christians. During the early days of Islam, a massive exchange of information took place between Christians and Muslims alike.

There seems to be little doubt that many scholarly scribes were quite busy doing both translation and transcription for the Church of Rome, the Royal classes and others in the middle east before the age of the crusades.

Translation, the Renaissance and the Reformation

During the late middle ages and the early renaissance period, the issues of canonical translation services became relevant once again. While translating bibles in their entirety was not approved by the church, movements throughout the west would ultimately end up successfully translating the bible into many of the common western languages.

It should be noted that even during the middle of the dark ages, there were still some translations of canonical texts that were approved by the Church of Rome. Carolus Magnus, Latin for Charles the Great, though more commonly known as Charlemagne, was among those granted some exceptions. Charlemagne was certainly zealous in his conversion of the Saxons, though he did at least have some of the canonical scriptures officially translated into German so as to provide access to the Bible to those who did convert.

Despite this and a limited number of other exceptions, translation of the Latin Vulgate was largely discouraged by the Church of Rome. Towards the end of the fourteenth century, a gentleman by the name of John Wycliffe produced English copies of both the ancient Hebrew scriptures and the Aramaic scriptures. At about the same time, a philosophy teacher by the name of John Huss produced a version of the Bible in the local language of the Czechs.

Wycliffe was briefly imprisoned, but it was during this time that the Papacy underwent some major challenges of its own, and with the help of supporters in England and the death of Pope Gregory XI, Wycliffe soon regained his freedom. Huss was not so fortunate, ultimately being burned at the stake.

While these may or may not have been the beginning of the actual reformation, there were certainly central to the eventual success of the reformation movement, at least in terms of getting the Bible readily translated for the average person. The sixteenth-century would see an even bigger push to have the Bible readily translated into common languages so that it would be readily accessible for the average person.

Erasmus managed only to translate the New Testament (or Aramaic scriptures) into Latin from Greek but expressed his desire that it be made available in English so that “even Scots and Irishmen” might read the scriptures, a demand which became increasingly popular throughout the reformation. About this time, two others in the form of Martin Luther and William Tyndale supported now by the work of one Johannes Gutenberg who in 1455 had invented and mastered the Printing Press.

Thus, throughout history, not only scribes, but translators, true believers, and even the heretics have served to help in the advanced translation of the canonical scriptures. The push by individuals of virtually every ideology and the advent of the printing press has elevated the modern Bible to the status of the most popular and most widely sold book in all of human history.