About the Pope

Catholic Church has a spiritual leader, while the state of the Vatican has a head of state. These two descriptions are filled by one person, the Pope.

Before being elected as pontificate, Jorge Mario Bergoglio looked after the spiritual needs of 2.5 million souls in the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires. When the College of his colleagues elected him on March 13, 2013, this Cardinal became Pope Francis and received huge spiritual duties, and a temporal smaller one.

The new Pope is the absolute head of the Holy See. In the strictest sense, the spiritual jurisdiction comprises only the diocese of Rome. However, Rome is where Saint Peter was martyred, and in the Catholic tradition, this Apostle became the first Pope. The current pope is his 265th successor in what is an unbroken line. Therefore, the primacy of papacy over other bishops exists, and the conflation of the Holy See with the rest of the Catholic Church, at least the highest of the Roman bureaucracy known as the Curia.

Holy See

The Holy See is, under international law, a sovereign entity. It has enjoyed this status since the Middle Ages, and it maintains diplomatic relations with most of the other countries. The state is also a member of different international bodies and has permanent observer status at the United Nations General Assembly. However, the Holy See is not the same thing as Vatican City, which has only been independent since the Lateran Treaty in 1929. The two entities have different passports and different official languages. Latin is the official language for the Holy See, while Italian is for Vatican City.

The Lateran Treaty was concluded between Mussolini and his fascist Italy, and the Holy See. This resolved the ‘Roman Question’ that arose in 1861 when the nearly unified Italy declared Rome as its capital and then escalated when Italian state took Rome from the Pope by the use of deadly force in 1870.

Without an independent Vatican City, the sovereignty of the Holy See would be like the one of the Knights of Malta. They have many ambassadors scattered around the world, while the Order is considered sovereign with no territory of its own. To avoid this, Vatican City got its independence, mainly to “ensure the absolute and visible independence of the Holy See”, and “to guarantee to it indisputable sovereignty in international affairs”, as it was stated in the Lateran Treaty.

Vatican City and the Vatican

Therefore you see, Vatican City is not what you think it is real. This is not the actual diplomatic interface between the Catholic Church and the world. That is the Holy See, and it has ambassadors with most countries. Vatican City is then the toehold of a sovereign territory that gives the papacy the peace of mind. It is the territory that shields the sovereignty of the Church.

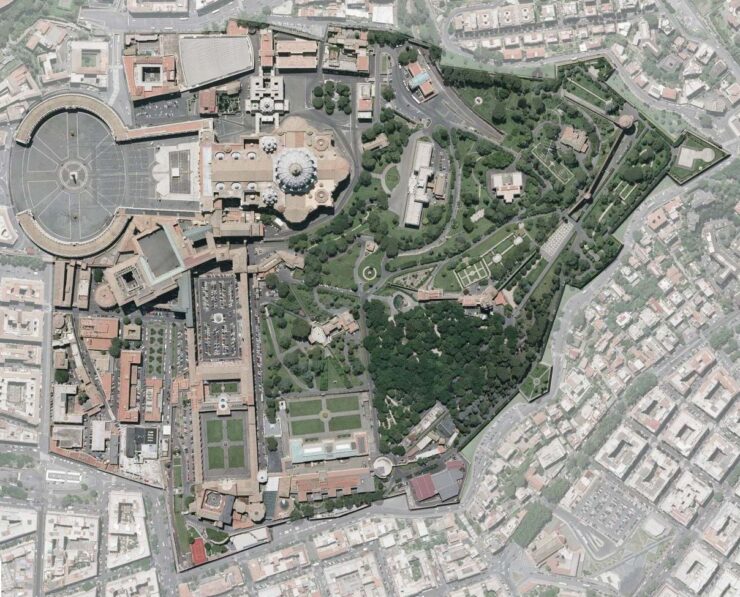

The Vatican is also not where you think it is. The borders of Vatican City are quite fuzzy for such a small country, the tiniest actually. The Papal State is the world’s smallest sovereign state, without considering the Knights of Malta. Vatican City is 108 acres or 0.44 of one square km. The second smallest state is Monaco, almost five times bigger.

Borders

So what are the Vatican City and Italy borders? Centered on Vatican Hill, the Vatican state border with Italy is around t 3.2 km long. In the south and west, the borders follow a 9th century Leonine Wall. Another recognizable feature of Vatican City outer limits is the St Peter’s Square. To the north of it, the border is the arrow-straight Via di Porta Angelica.

Counter-enclaves are rare, and the ‘discovery’ of one in the Vatican would have been something spectacular. Unfortunately, the Fontana enclave tis not it. “[I]t just means that the entry has been created by a WikiMapia user in the Italian language”, as a BorderPoint contributor said.

WikiMapia map reveals another interesting zone between Italy and Vatican City. It is an external territory on the southern edge. This holds the House of Hospitality, the Palace of the Holy Office, the German College and German and Flemish Cemetery, the Santa Maria della Pieta in Camposanto church, and two-thirds of the Paul VI Audience Hall. The area is a part of Italy but has an extraterritorial status, which means Italian laws do not apply here. Mon many maps, it is shown as a part of the Vatican.

Some maps show the extraterritorial zone on the left of St Peter’s Square. Others show a curious zone to the right of the square, a small strip three meters wide and 60 meters long, that goes along the northern colonnade of the square. Italy says the Lateran Treaty determined this as Italian territory, but the Vatican disputes it of course. The difference has been unresolved since 1932 when an Italian-Vatican commission agreed to disagree.

The fuzzy and intriguing border between Italy and the Catholic Church does not end at the Bernini colonnade, nor the outer limits of the Vatican. Actually, there are numerous churches and other special buildings scattered throughout Rome, which are offices of the Roman Curia. They have the extraterritorial status by the Lateran Treaty but are not a part of the independent Vatican City. There is a map from a 1931 issue of the Geographical Journal that shows the extraterritorial areas of that time.